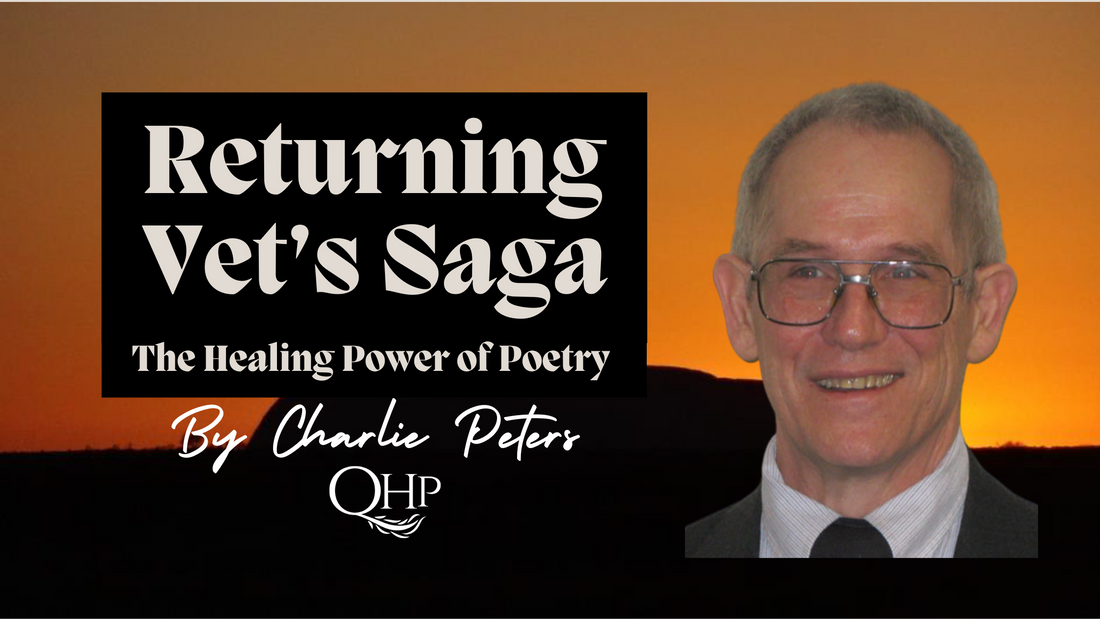

Returning Vet’s Saga: The Healing Power of Poetry is my third and latest book, to be published in January 2025. Written by a Vietnam Vet who served in the United States Navy from 1969 through 1975 (primarily on submarines), it is a compilation of my poetry writings, predominantly during the 1990s. The last poem in the book, Returning Vet’s Saga, was the beginning of it all—the first poem I wrote. It took over a year to complete, and while I did not intentionally set out to write the poem, it just happened.

Unbeknownst to most of those around me, I did have a problem after being discharged from the Navy. It was a problem that did not arise while I was in the Navy. I would wake up in the middle of the night from a nightmare, which usually had something to do with being chased or crushed. Eventually, my wife would wake me up when she sensed something was wrong because my hands would be flailing around in my sleep and wake her. Sometimes, she had to shake me pretty hard to wake up. I would be drenched in cold sweats and not know where I was. I am very fortunate because, at this point, many of the vets’ wives left them after their return home.

Let me elaborate just a little about the cause of those nightmares. I know the cause of my being plagued by being crushed and/or chased, and it has to do with prayer. Whenever a serviceman is in serious danger of losing their life, there are usually three distinct prayers they offer up if there is time. The first level is praying that you might get safely out of the situation. The second level is praying for the safety of your family and loved ones. The third level is when one prays that their demise will be quick—not pain-free—just quick. I have offered all three.

There were times when I would be right back where I was when I was in the thick of things. The cause could be as simple as a sound, a smell, a flash of light, a scene in a movie, a tense situation while driving in rush hour traffic, or even a commercial on television. Sometimes, those moments would come when watching a particular scene in a movie, when the tears were dropping from everyone else’s eyes, and no one paid any attention to me. Sometimes, one of my children might say, “What’s wrong, Dad?” and I would say, “Oh, nothing, it is just something in my eye.”

My book is the story, or poetry, of one returning Vietnam Vet’s experiences, shared in common with many returning Vietnam Vets. Upon arriving home, all Vietnam Vets and Vietnam-era vets were grouped into one classification and treated the same. It took fifteen years to describe what I had felt after returning from the military, then a few additional years to complete this work. As I started to write the original poem, Returning Vet’s Saga, tears ran down my face—it was a “River of Tears.” When I finished writing the poem, it was a trickle of occasional tears. Each veteran who has received that poem cannot read it without shedding a tear or two.

As some later told me, “The floodgates of the heavens opened up.” The usual comment they make after reading this poem is, “I thought I was the only one that felt that way.” The highest compliment for this poem was from the girlfriend of a Vet. She obtained a copy of this poem to give to her boyfriend. She told me that when they broke up, and the Vet left her, he took the copy of the poem with him. Another Vet paid me this compliment: “All these years, this is how I felt, but I could not put it into words.”

Most veterans who read the following poem ask me if they can keep it, and naturally, I say, “Yes.” When those who are not veterans read the poem, they usually hand it back and say, “It was good.” If you read the poetry in my book and do not fully understand, don’t feel bad because only those who have served or who have gone through very traumatic experiences themselves (abuse, bullying, rape, unwarranted violence) can understand what these poems mean.

Those who did not serve cannot thoroughly understand the feelings of those of us who did. Many of us who served during the Vietnam War were drafted, and our lives forever changed. Whatever it was called—Boot Camp, Basic Training, or Flight Training—it was the life of a recruit into military life. In ten, twelve, or even sixteen weeks, we changed from the person we once were into a fighting military machine… a killing machine. During that several-week period, former identities were lost and replaced with new ones—ones the military wanted us to have. There were no choices; it was to change and be like the rest.

The military never retrained us to stop being killing machines—we were expected to do all that on our own. Sadly, many of us never retrained to be our former selves! After Vets returned, there were many sleepless nights, and the light sleeping went on for ten, fifteen, or more years, being awakened by the slightest noise or touch. Most all suffered and may continue to suffer periods of depression (though others may not realize it). Instantly, they may be flashed back to where they were serving: by a noise, smell, word, or even action. Even today, the tears still come to their eyes, not as often, not as long as they first did, but they still come back occasionally. My poem, River of Tears, conveys how depression can come from nowhere and increase relentlessly. When discharged, some were told, “Don’t tell anyone where you have been or what you have done. If you do, we will come after you, and you will be tried in a military court, not a civilian court.”

Many often think about what they would have become if they had not served. All those who served gave up something they were never given back when they returned. No matter where they served, none returned the same as when they had left.

One day, an individual I did not know asked me if I was a Vietnam Vet. I said yes while thinking, “Oh, well, here it comes again!” Then they said, “I am glad you survived and came back.” It hit me like a baseball bat between the eyes. I had never heard those words and broke down on the spot. It took me a while to regain my composure. They apologized for bringing back some bad memories. I explained that I had come to accept unkindness because kindness was so seldom received (concerning my being a vet) that I didn’t know how to respond. So, to all vets who have returned, “I am glad you survived and came back home. Welcome home, Vets!”

This book honors all who served and returned and those who served and never returned. All of you veterans who returned are heroes. You are heroes because you were not afraid to put your lives on the line, something that most living in this country today have never done. You put up with much while you were in and have put up with even more since you returned. You Veterans truly are the great American Heroes!

War does some strange things to people. Before I was drafted, I went by the name Charlie. After I was discharged from the Navy, I didn’t allow anyone to call me that. It was not something I did intentionally; I didn’t feel comfortable being called Charlie. After I was discharged, I went by the name Chuck. For over fifteen years, I was Chuck. Then one day, I was talking with an old friend who also served in the Navy during the same period I had served. I called him by the name I remembered, and he corrected me, saying, “I am not called that anymore!” Then we talked about why we were now called by different names. I have learned that many changed the name they were called after they were discharged from the military. It is possible that our old names reminded of something we once were, something that we no longer were, and changing our names helped ease the pain of what we would never be again.

Many youths watch their parents suffer through the aftereffects of war. The parents feel the child cannot understand what they have been through and, therefore, never talk to the child about their suffering. The child, on the other hand, sees their parents cry. The child sees the parents get angry and may even know the parents get abusive. Children may not understand the war, but they certainly do thoroughly understand the aftereffects of war. Maybe this book will help those who watched their fathers suffer better understand why their fathers were the way they were. (Read the poem A Man Less Than His Best.)

There were over 58,000+ (the count is now up to 59,479) who lost their lives in the Vietnam War. That is only the tip of the iceberg. Each one of those had families that were also affected: a wife, a girlfriend, children, a mother, a father, a brother, a sister, aunts, uncles, cousins, and friends. It was not just surviving veterans who suffered the loss of the 58,000+. Veterans only knew the dead Vet for a few months, and the loss for them was never forgotten. But, never forget, each Vet who died had family and friends who had known them for a while. Those family and friends lost someone who had been near and dear to them for twenty years. Those family members and friends also suffered a great loss. This book of poems is dedicated to the family and friends of those who were slain in Vietnam and those who later lost their lives as a result of that war.

When we are born, we inherit a flee or flight instinct. The instinct works naturally, but it can either be enhanced (to better protect us) or reprogrammed or retrained. That instinct is supposed to protect us from harm. If it is reprogrammed, we no longer have a built-in, “God-Given” self-protection system. That instinct can be retrained so that we either always flee or always fight. In other words, the natural “flee or flight” instinct becomes either a “flee only” or a “fight only” instinct. For those who have served in the military, especially combat veterans, that natural “flee or flight” instinct was retrained to be a “fight only” instinct. When the vets were discharged from the military, they were never retrained. Their “fight only” instinct was not reprogrammed to be a “flee or fight” instinct. This “fight” instinct they now had would follow them for the rest of their lives unless, at some point, they were reprogrammed to a “flee or fight” balance. The “fight instinct” is carried over into every aspect of their lives. Their only reaction to confrontation would be to “fight,” whether verbal or physical. Their instinct to fight enabled them to survive a war. Without reprogramming, they know no other response; it is fight only. Fleeing is not an option anymore.

Before entering the military, jobs were plentiful during the Vietnam War. There were always summer, part-time, temporary, and full-time jobs. After graduating from high school, some went on to college, and others found work that eventually led to a career. Many were able to find work in areas that they enjoyed. Some even looked forward to working for one company until they retired. All, of course, entered the job market at entry-level positions, eventually leading to other positions and, hopefully, a career. Upon entering the military, we passed the entry-level positions and were on our way to a career. Some of us were drafted, others enlisted, and all left our jobs. However, after leaving the military, we did not enter the job market where we would have been had we not been in the military. Nor did we re-enter the job market where we had left off when we entered the military. We had to start over and accept entry-level positions.

Life is a gift that all should appreciate. When times are good, it is greatly appreciated. But, when times get bad, it is something that is so easily forgotten. When times aren’t good, we may think of a final solution. It is a permanent solution to a temporary problem. Though the problem may be temporary at the time, it may not be a temporary problem for us. Maybe this book might help some to remember when the times aren’t so good that maybe, just maybe, it is a temporary thing, and there is no need to make a permanent solution to a temporary problem.

This is the background for my poetry and the book Returning Vet’s Saga: The Healing Power of Poetry. When I started writing poetry, it was just for me. No one else was going to read my poems. But, I happened to show one Vet a poem I wrote, and he showed it to others, and now I am showing my poetry to the world. People have encouraged me to put my poems in a book over the years. I finally did, and I want to thank each and every one of you for encouraging me to do that. It took me thirty years, but I finally did it. I now share with you what was originally written for my eyes only!

About Charlie Peters

Charlie Peters has been married for 50 years and has four children, nine grandchildren, and thirteen great-grandchildren. He accidentally started writing poetry in 1990 and discovered that poetry proved to be an outlet to release the frustration of PTSD symptoms. He wrote poetry for about ten years. Two of his poems were runner-ups in national poetry contests: “A Man Less Than His Best” and “Stairway.” Then he shifted his writing efforts to political commentary and satire, and two of his published books resulted from those commentaries: “The National Debt? The Sinking of America!” (2008) and “TEA Time Has Arrived ‘We the People’ Versus Washington Bureaucracy.” (2009). He has now decided to publish many of the poems he wrote in the 1990s, and this book is a result of his poetry writing.

“Returning Vet’s Saga: The Healing Power of Poetry” is a work that may appeal to those suffering from unexplained moments of anger, frustration, frightening nightmares, and unexplained moments of depression, which a downpouring of tears may accompany. The author experienced all of those symptoms after returning from the military, and the symptoms lasted for about fifteen years before those symptoms even had a name, which we now call “PTSD.” The author found that a sound, a smell, a spoken word, another person's voice inflection, or something as simple as a commercial on television can trigger an episode of PTSD.

There is no magic in poetry. However, the magic comes in putting feelings to paper, coming directly from the heart and completely bypassing the brain. We may not think of ourselves as poets, but if we just let the words flow, we may find that we are, in fact, poets of a special kind.

This book ends with the poem that got it all started.